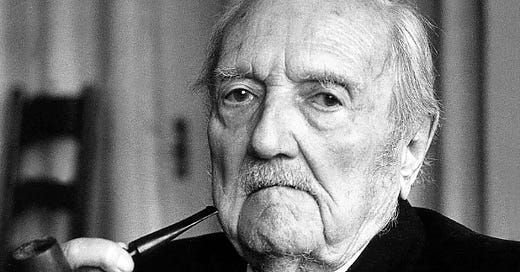

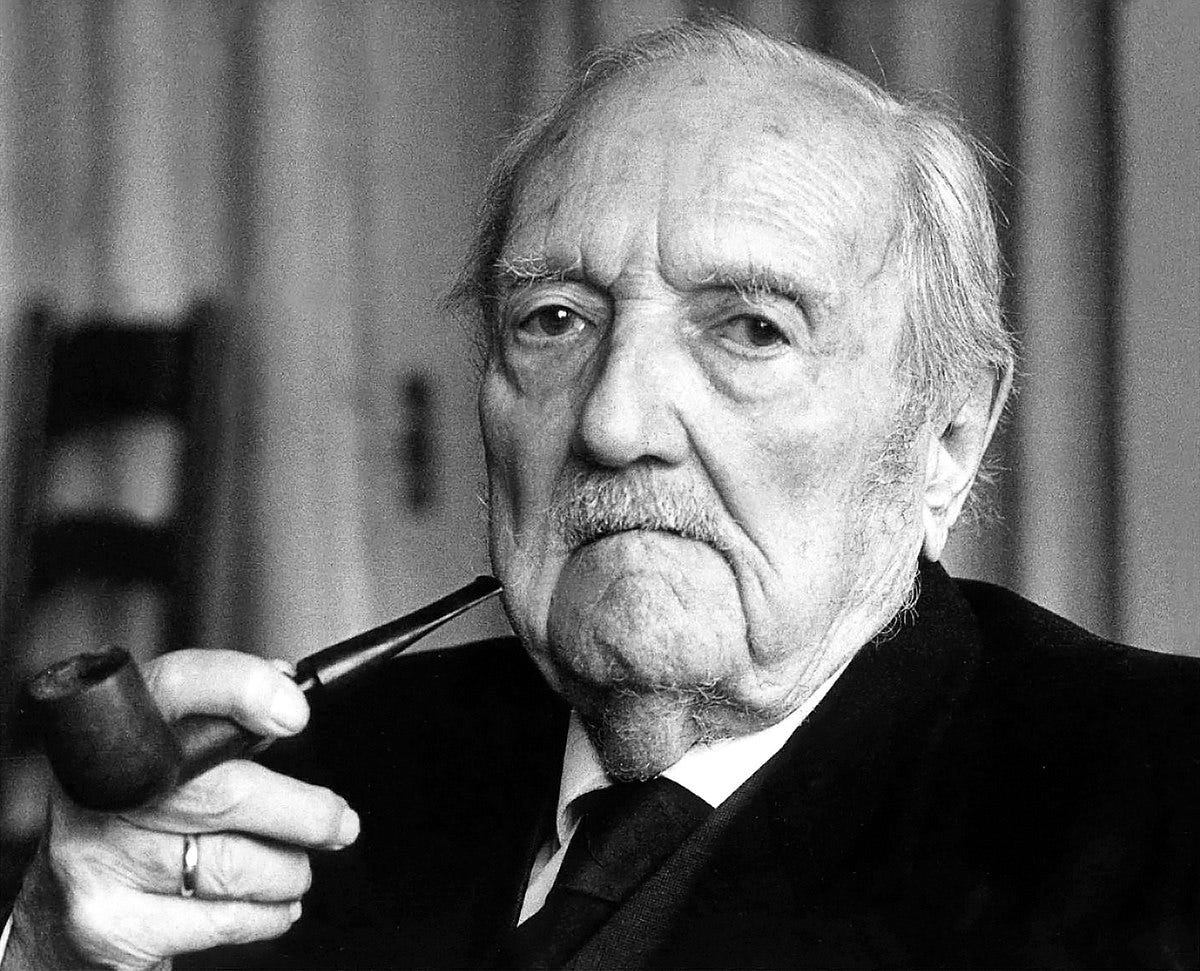

A little over a year ago, I was introduced to the name “Bultmann”, and it was not a friendly introduction whatsoever.

It was in one of my favorite classes of my spring semester, and a student said something to the effect of “Read anything you want as long as it’s not Bultmann!”, to which I responded, “What’s wrong with Bultmann? Who is he?”. The student just looked and me and shook his head. The professor giggled and seemed to agree.

After class, I asked a mentor of mine who his least favorite theologian was. “Probably Bultmann”, he replied. When I asked him why, he said “He and others made a whole mockery of the faith.”

I was blown away by these strong accusations against a man who I had never heard of. His name sounded German, and he was referred to in class as a contemporary of Karl Barth, but nothing else was said about him other than these insults to his character and theology. It was almost assumed that no faithful Christian seeking to do good theology would even entertain his work.

Being the rebel that I am, and someone who detests the idea that the only people worth engaging with are those who make evangelical Christians comfortable, I decided to do my own research on Bultmann. From the brief things that I read, he seemed like someone who was rather boring, and given that I didn’t have a good taste in my mouth about him, to begin with, I decided it would be best to just ignore him.

Many months later, with the help of my friends David Congdon and Alex DeMarco, a brilliant Bultmann scholar, and a badass book editor and lay theologian, I decided to give ol’ Rudolf a try.

Alex gave me Jesus Christ & Mythology as an early Christmas gift, and though I expected a book full of heretical treatises, what I found was a beautiful expression of how so many Christians post-Enlightenment were and are wrestling with the Word. It made me think deeper, pray, and question more. It also made me enraged at how cruel, uncharitable, and slanderous the accusations against Bultmann were.

No one in good faith deserves to be misrepresented and have their name dragged through the mud, no matter how much we disagree with what they say.

For brevity’s sake, I’ll break down my review of the book, not by chapter, but by key takeaways.

Bultmann’s Central Question is Essential

Perhaps the most important thing about Rudolf Bultmann’s theology is not the conclusions he comes to, not his theological proposal of “demythologizing” the Scriptures, but the questions he raises to get to that point.

Theology is a constant conversation as well as an embodied and lived experience, and Bultmann invites us to wrestle with both the conversation and its implications.

Take his central and defining question as one example. To summarize/paraphrase,

Jesus Christ existed in an ancient time and place that was conceived of and defined by mythology. People had mythical concepts of just about everything from sin and redemption to demons and spirits to resurrection and eschatology. Now that we have scientific answers to many, if not all, of these questions, what do we do with Jesus’ life, preaching, and the New Testament theology that follows?

To call this question unavoidable would be an understatement. I would go so far as to say that the question of what Christians are to make of modern science’s developments and advancements in light of the Gospel message is one of the primary questions of all Christians living in the developed world, whether we experience that development in its fullness or not.

Whether we like it or not (and I happen to dislike portions of it), everything we know about the world changed with Sir Isaac Newton’s “Laws of Motion” in 1687 and Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. We who benefit greatly from the medical, technological, and scientific advancements made in the centuries following these two giants cannot simply ignore and wish away these things when they run into the brick wall of our faith.

For Christians, we are called to remain faithful, and remaining faithful means wrestling with new things we learn about each other, the world in which we live, and the God who brought all things into being. Is the God we worship anti-intellectual? Is He intimidated by Newton and Darwin? Can we only interpret the Word of God from a purely mythological perspective? Bultmann says “no”, and I agree with him.

If we throw out science in an attempt to “appease” God, we project our own insecurities onto God, who is ultimate security Himself. We make Him into our image instead of allowing Him to make us into His. We also impose a false dichotomy onto God, setting up science and its methods as rivals to God. But, if we are witnesses to the Word, we know full well that God has no such rival and that science and its methods are His creation and sit under His authority just as much as we do.

Moreover, we have all seen the consequences of a “faith” that tells us to ignore our God-given senses in theologies that promote anti-vaccine conspiracies, COVID-19 denialism, and other beliefs that lead to harm and death. We’ve seen the consequences of juxtaposing God and science, and it isn’t pretty.

Surely a God as beautiful, loving, faithful, intentional, and almighty as ours can hold all of the world and the cosmos, in all of their natural processes and breathtaking discovery, in His divine hand. I think Mr. Bultmann would agree.

Demythologizing Can Make Us Better Disciples

A majority of Jesus Christ & Mythology is not Bultmann’s developing of his most well-known and provocative theological task, “demythologizing”, but rather defending it and restating it in light of the often uncharitable criticism he received from mostly American theologians regarding it.

For Bultmann, “demythologizing” is the Christian task to uncover deeper truths of the Gospel message by not taking literally the sensational accounts of demons, spirits, the underworld “below”, the heavens “above”, and others that we see throughout Scripture, but rather on what these symbolic accounts mean for us as believers today.

In Bultmann’s own words, it is the task of “eliminating a false stumbling block”, that often leads to Christians in the modern age to reject their faith in light of scientific advancements in favor of the “real stumbling block; the word of the cross”.

For Bultmann, the Christian message is not something that one can either accept or reject by sacrificing their intellect or by reason. Rather, it is in a totally different category altogether, kerygma.

“ …that is, a proclamation addressed not to the theoretical reason, but to the hearer as a self.”

Kerygma is what one hears when the Word is proclaimed. For Bultmann, is this event of proclamation on one end and hearing on the other, that invites people to follow Christ. Only when Christ’s life and work are translated and manifested in a direct personal experience can one truly come to faith.

Demythologizing means that we in the modern age need not accept the ancient worldview as literal fact, nor can we afford to limit the truth of the Gospel to ancient concepts. The Gospel lives and breathes in our lives right now, and invites us into discipleship, into service of the cross.

This is why the “real stumbling block” for Bultmann, is the “Word of God”. Because the “Word of God” means that God, and not humankind, has the final word on human existence, human beings cannot pretend that they are really “masters of their own destiny”, no matter how much scientific discovery they may come up with. The Word of God calls all human beings into total submission to God and God’s plan for the world, that we would be guided by love, grace, compassion, mercy, justice, righteousness, obedience, and service.

Bultmann acknowledges how difficult this task is in the modern world. We would rather just believe in our willpower, our own intellect, our own conscious. But that is not what the kerygmatic Word calls us to. We must always look to God’s will, which is not that we believe that this or that mythological event occurred in human history literally, but rather that we follow Him today.

This looking to God and knowing God through our personal encounter and submission to His will is what makes Bultmann call demythologizing an “existentialist interpretation”. We only encounter God in our natural faculties, thus Bultmann’s concern is what we do with that encounter existentially. To be a disciple is an existential decision for Bultmann, and for me too, as someone who was theologically baptized in the existentialist theology of James H. Cone.

Therefore, rather than making God a mere concept, or making ancient belief systems conform to our modern view of knowledge, Bultmann uses demythologizing to make the Christian a better disciple. Once we focus on following Jesus, nothing else matters. We are on the right path.

Where Bultmann & I Differ

As much as I love and endear myself to Bultmann’s theological task, I cannot find myself in total agreement with it.

For starters, I believe in the supernatural and I believe that the ancient worldview of the Gospels does speak to things that actually happened in human history. I believe that Jesus’ resurrection was a literal, bodily event, I do believe that He ascended into heaven, and was incarnate of the Holy Spirit through Blessed Mary, the whole nine yards of Nicene Creed orthodoxy.

I can’t quite explain “why” I believe that. I wasn’t there, after all. But I have seen God move and work in powerful and miraculous ways.

I was born three months and fourteen days premature, and the doctors told my parents that there was a fifty/fifty chance of my survival. A little while after, as I was in an incubator fighting for my life, a man walked up to my dad in his old neighborhood and said “God’s got your son”. Praise God, the man was right! I survived and was released from the hospital shortly thereafter. My dad never got the man’s name and no one he knew ever saw him again.

Was this man an angel? I don’t know, but I do believe that God spoke to him and that his words were God’s comfort for my father, who, though not a church-going or religious man, prayed alongside my mother every day for my full recovery.

I believe that throughout my life, as I navigated a childhood marked by my sense of call to service of God and the Church, God has spoken to me many times. Have I seen Him in the flesh? No. But I believe that I’ve encountered Him through Christ’s message of hope and liberation articulated so well by James Cone when I was in one of my darkest spiritual seasons of anguish.

I believe that when I was 17, God made Himself indescribably known to me, something that led me to years of joy and to wrestle more with Him, to theologize and question, to explore and pray, to come out as Queer, to commit myself to the liberation of all people.

I can’t prove any of this tangibly, and this is only my experience of God. But I know, I just know, that God has revealed Himself to me in both natural and supernatural ways. I know of many people in my life and far beyond it who can say the same thing. I’m not so quick to dismiss mythology entirely as not “literally true”, for all people. Many of us believe in some forms of mythology because we’ve witnessed it!

I don’t necessarily believe Bultmann would dismiss any of this. His heart was pastoral and gentle as well as scholarly and serious. Who knows? Maybe he’d share some experiences of his own with me!

But, if demythologizing has to be all or nothing, a zero-sum game, I’m not sure if I buy it. I sincerely believe that Bultmann’s task can be celebrated and embraced and explored without discounting the spiritual experiences of millions of Christians, mainly concentrated in the Global South, who infuse their own culturally-specific encounters with God with joyous worship, prayer, healing, and social praxis.

Surely, these believers are onto something. Surely God has spoken to them. Surely God lives and breathes in their lives as much as he does in ours in the West. Surely we cannot compartmentalize, exoticize, or tokenize them (as so many white evangelicals love to do), but we also cannot seek to interpret them through Western lenses. Our epistemology, as followers of the brown-skinned Palestinian Jesus, must hold space for them and their experiences too.

With demythologizing and supernatural encounters, I believe holding both in common to be the most compelling and loving course of action.

Bultmann loved Jesus

The most striking takeaway I had from Jesus Christ & Mythology, wasn’t that Bultmann was a genius (he undoubtedly is) nor was it that I found his demythologizing task to be deeply compelling (though I certainly do and am grateful for it).

Rather, it was that everything that I had been taught about this man, Rudolf Karl Bultmann, was a total and complete lie.

Not only did Bultmann not “make a mockery of Christianity”, but he was in no way, shape, or form, a “heretic”. Such a cheap shot against a man who can only be understood in light of his context, who resisted Hitler’s Third Reich, who wrestled with the Word until he died, and who preached eloquently and evangelistically about the grace of God, strikes me as a sinful slander.

We are duty-bound, those of us who wish to follow Jesus with our mind, body, and souls, to be deeply charitable and full of grace to all people, no matter what they do or say. Even the worst people imaginable or worthy of that.

When it comes to theological discourse, our calling to be charitable and gracious does not change. Even when we disagree with someone, even when we believe that someone is promoting harmful or even evil and idolatrous theology, we are called never to attack their character, but to critique, and even sometimes destroy, their ideas.

In the case of Bultmann, this calling has been utterly unfulfilled. The attacks on his character have been merciless, both in his life by his contemporaries and in the years following his death. This is completely unacceptable, not only because of how these critiques are issued but in the utter falsehood of them.

Rudolf Bultmann loved Jesus. That is what propelled him to write and think the way he did. He wanted to proclaim that Jesus, the Lord of the world, was still meaningful and still impactful and still Lord, even in the modern age. He wanted us to think critically about modern New Testament research, about the role of mythology and ancient ideas in our faith, about how

we could still follow Jesus even if we differ on how we do that.

Do I agree with every answer Bultmann comes up with? Not at all! But do I deeply respect him as a theologian and a witness of my faith who should be read by any seeking to preach the Word, as I do?

Yes, wholeheartedly, yes!