Oh, don’t you want to go to that gospel feast?

That promised land, where all is peace?

-Anonymous Negro Spiritual

I wish I knew how it would feel to be free,

I wish I could break all the chains holding me

-Billy Taylor

I am one of Chicago’s Black sons. There are many of us, tossed to and fro within the city’s borders, but most of us live in one of two places; the West Side and the South Side.

The West Side is a place of a simple, immaculate beauty. In North Lawndale, my first neighborhood, mornings greet us with a gentle sunrise, illuminating the top halves of the brick-layered and stone houses that line its streets. The smells of bread, bacon, and coffee permeate the air, and students carry their large backpacks to school, and with it a casual joy reflected in their laughter. Their anxious parents wave them off, their long glances as their offspring walk away from them serve as long prayers. “Cover them Lord”, they whisper.

West Siders are a progressive people; they yearn for what freedom, justice, and solidarity really means and really feels like. Their barbecues are open tables, their homes don’t turn anyone in need away. Joy, therefore, isn’t a scarcity to be hoarded but a holy contagion to be caught and lodged in one’s soul. They are naturally skeptical of authority, and lurking politicians with their shameless solicitation of electoral support will be met with loud questions of What have you done for me lately?

West Siders are a conservative people. They get on their knees and go to God in prayer because they know from “whence their help cometh!” They put on their purple hats and navy blue suits for Sunday Morning worship and they resent when the young people nod off and goof off in the pews. They believe in getting a job and keeping it, in going to school and staying there, and they loathe excuses and insincerity (“get the fuck outta here with that!”, you’ll hear if you listen long enough). They are a “bottom line” group of people; things are what they are.

These communities, in which I wandered and lived, never lacked love, character, or vibrancy, but peace: a peace that comes with the commitment of resources, the opportunity to grow and be mobile, the guarantee that equal justice under the law applies to you, too. The absence of this peace—manifested in the dilapidated housing, the vacant lots, the drug needles, the run-down liquor stores with shattered glass, the garbage bags that sheltered the unhoused against the cruelty of Chicago winters, and the “urban renewal” that renewed nothing more than a promise of permanent displacement—existing as a living contradiction to its beauty, and made it nearly impossible for this community to rest, and it was in this restless state of being that I became a writer, a thinker, and a preacher, before I even became a man.

This country, despite its greatness, has always had a complicated and uneasy relationship with freedom.

After George Floyd’s murder, it appeared as though the world (the white world anyway) took a greater interest in what Cornel West calls, “the chocolate side of town.” Black America, its own nation under God, presented its white neighbors with a prime opportunity to uncover the realities they’d spent their whole lives ignoring. Some of them took this charge seriously, and did their work. They disentangled themselves from the cords that prevented them from moving, they listened rather than merely heard, they didn’t just acknowledge, but sought to really see. They understood, and sought to get their peers to understand, that they weren’t the center of the story, but vital participants in its ending, and that a just world meant freedom for them as well as freedom for us. They understood that the idea that we are all bound together was a fact as real and true as the realities of the broken country in which we live.

Most of white America, however, did not follow the examples of their braver citizens. Their apathy and condescending indifference gave way to an exploitative voyeurism that couched itself in progressive language like “listening to Black voices,” wherein centuries of deep-seated trauma and pain depicted in various art forms seemed to present a convenient cover for a nation that refused to confront and atone for it’s past but desperately wanted to appear as if it had. But the truth, which always prevails in the end, remains; gawking is a woefully inadequate successor to neglect.

Black words, Black music, and Black people were valid both on and off the page well before white eyes glossed over them, and the Black story is not solely one of trauma and pain. Moreover, the period of public mourning and temporary recognition that passed as a “moral reckoning” is woefully inadequate for a country that wears its unrepentant sin as a badge of honor. Nevertheless, here we are; still too far away from the Hills of Zion.

Freedom has become something of a persistent occupation; a trade which we have not yet mastered, with disastrous results. From beer, to freedom of worship, to tobacco plantations, to slaves, to emancipation, to “separate but equal,” to “praise the Lord and pass the ammunition, to “we shall overcome,” to Black power, to the modern imperial experiment, this country has had a tumultuous relationship with the concept of “freedom.” We are yet again asking the same question today as we were toward the end of the 18th century; whose freedom?

I think the Scriptures, with which this country also has a checkered relationship, can serve us well here. St. Paul writes in his first epistle to the church in Corinth,

“Though I am free and belong to no one, I have made myself a slave to everyone, to win as many as possible. To the Jews I became like a Jew, to win the Jews...To the weak I became weak, to win the weak. I have become all things to all people so that by all possible means I might save some. I do all this for the sake of the gospel, that I may share in its blessings.” (1 Corinthians 9:19-23).

The use of St. Paul’s freedom then, is the work of solidarity with others; of tethering oneself to a community, of the active choice to belong to someone, not by means of coercion but through the even more powerful act of self-sacrifice. This is, as St. Paul alludes, the mechanism by which God gives salvation to the world.

And yet this concept of freedom is so foreign to American ears, as citizens of an individualistic Western world. Community life has become less and less important to our own personal lives, and we certainly don’t view it as a source of any kind of “freedom.. Our workplaces exhaust and exploit us, we are far too easily enamored with vanity to understand our own value and beauty and that of our neighbor. Our churches and places of worship no longer provide the respite we crave; we are a sick country, filling the voids of our own lack of meaning with more war and weapons of war, with more wealth and more unequal distributions of it, with more hatred of the foreigner, the unhoused, the addict, the “scary” Black boy, the “perverted” gays and drag queens, the trans kids, the Jews, and whoever else we can find to scapegoat for our problems.

We aren't truly “free people”; we are a people tightly bound to our collective sense of inadequacy under the illusion of freedom.

When I was growing up, my teachers made it a point to emphasize to us that we, a bunch of Black kids from the inner city, were citizens of a “free country.” We weren’t the Chinese or the Russians, living under authoritarian regimes where journalists went missing and opposition leaders died mysterious deaths. And we weren’t those dreadful Arabs living in countries where being a Christian was a crime. We ought to be thankful, they would say, for the freedoms we enjoyed.

I’d be lying to say that these assumptions about our supposed “freedom” were limited to the imaginations of my white Christian teachers who lived in wealthy suburbs. I frequently heard these same echoing’s among the Black and Latino middle-class, both groups determined to obscure their displaced and marginal identities in the context of a loyal patriotism.

But behind these veneers sat a constantly confounding reality, a reality I couldn’t ignore even if I tried; the realities that made up the experiences of my invisible siblings, the reality of my own city, my own country.

I couldn’t ignore the unhoused, because the unhoused were everywhere. They slept in the viaducts, on the filthy concrete floors underneath them, in soil-soaked vacant lots, in alleys littered with debris. They always asked for money, but I was supposed to say no. They occasionally asked for food, but I never had any. Most of the time, they didn’t ask for anything; they could sense that their mere presence gave license for silent ridicule.

I couldn’t ignore the addicts, because they stood on the street corners, looking paler, thinner, and more terrified every time your eyes just so happened to meet theirs. You couldn’t tell what was going on in their minds, it was something of a mystery, but you could see what was happening to their bodies. Eventually, they’d disappear, and you hoped that they would find some final rest in the grave.

I couldn’t ignore the migrants, because they painted our North Lawndale apartment when we were broke, their kids invited us to play with them when we didn’t have any friends in the neighborhood, and they made sure to greet us when we left for school and work and welcome us home every evening, without fail.

And I couldn’t ignore the workers, because they paved the roads, cleaned the bathrooms, prepared the food, repaired the car parts, clocked in from 8:30-5, filled out reports, delivered packages, answered customer service questions, wiped viruses from computers and still knew no rest until the outstanding balance on their rent was zero, groceries were in the house, and the water and lights stayed on. I couldn’t ignore them because we were them, and it seemed that no matter how hard my mother and father worked, we were still without the peace of mind that our quintessential and gratitude-demanding “American freedom” promised us.

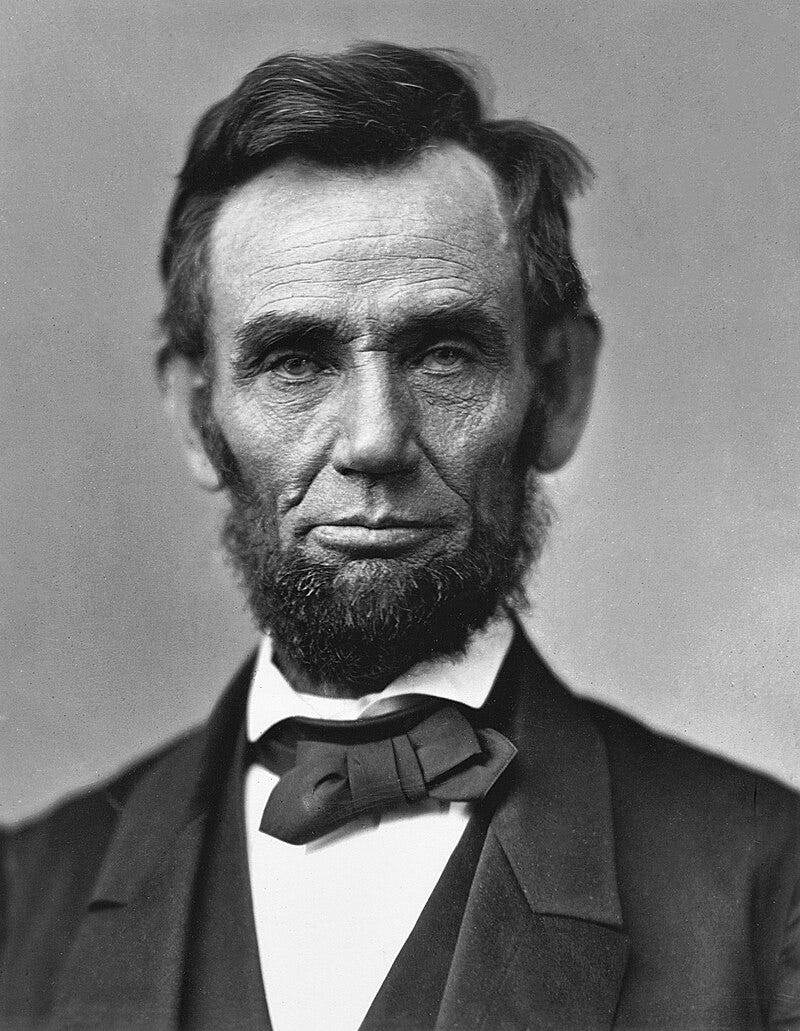

At Gettysburg, we were told that ours was a nation undergoing a “new birth” of freedom, and yet nearly two centuries later we have yet to embrace any idea of freedom that truly liberates and enfolds all of us. Our individualism is so deep, our moral and spiritual poverty so entrenched and our souls so tired, that we cannot imagine the meaning of a “true freedom.”

But, if we believe the words of the old American anthem, that true freedom is neither silent nor static, and is not some natural occurrence but must be allowed to “ring.” then we must abandon our apathy, rest through our exhaustion, and re-imagine our collective freedom. Our survival depends on it.

What does this true freedom entail? Who has conceived of it? What possibilities emerge from it? To answer these critical questions, we must turn to the origins of our collective “unfreedom”; the reality of racial capitalism, rooted in white supremacy and coloniality, that first manifested itself in the genocide of the indigenous peoples of the Americas and then in the chattel enslavement of African people.

In other words, in order to imagine what an authentic freedom entails we must go to the cotton fields, the plantations, the “big houses,” the swamps, the ports; the sites of generations of misery and unbearable suffering for Black people. They have something to tell us about freedom, as those for whom it was not an abstract principle relegated to the discourses of the academy, but a concrete reality which only some would see but all would imagine and dream of.

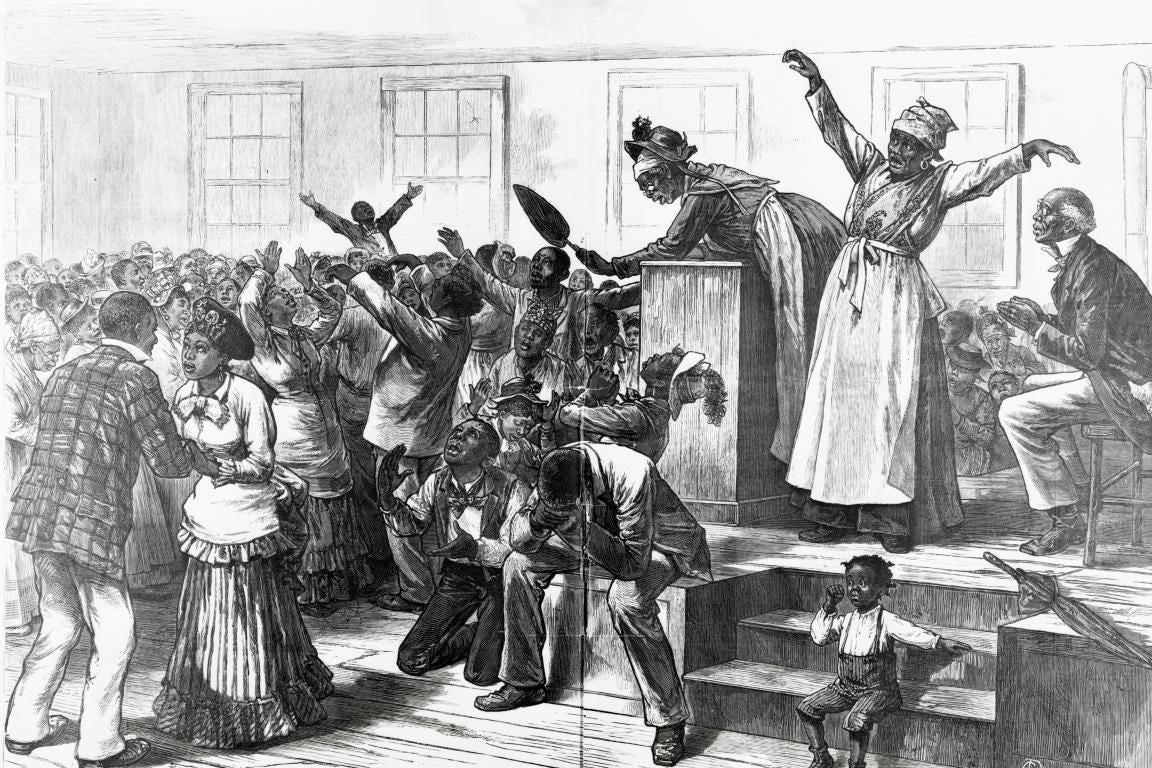

In the churches of the ancestors, there was wailing, shouting, dancing, stomping and weeping. These suffering saints, who could not read the Scriptures nor write in their margins, who had been told since birth through word and deed that they were destined for eternal subordination, whose homes were “all over Jordan” and who longed to “cross over into campground”, encountered the salvific power of a freedom for. In these wood buildings with dirt floors, in the midst of the incarnate hell of the plantation, the Spirit moved and worked within their souls, and joy and faith was their freedom. Freedom from had gotten them off the plantation, but freedom for gave them the faith to shout “Glory, hallelujah!”. For that brief few hours, they encountered what would be an eternal reality; their food and stay in the Hills of Zion.

What has been lost in the American tendency to either glorify or be mortified by our past is the view of history in which these ancestors are not distant relatives of an unfortunate race, but spiritual elders filled with wisdom, grace, and an unshakable faith. They’ve been my North Star, and they must be ours if we are to create a truly free America; in which my freedom and that of those I know and those I don’t are bound together, in which freedom for one another outweighs our desire to be free from each other, and in which that which makes us unfree, all of our money and all of what’s left of our power is washed away like the stains of sins in a baptism, in which we all know how it feels to be free.

The achievement of this freedom is a radical endeavor, one of overturning and uprooting, and one of a refusal to accept and be content with that which keeps us in chains; an end to our racial capitalism and our patriarchy, the dissolution of our armies and weapons, the sunsetting of our carceral systems and the beginning of real restoration, and an economy that uplifts us, our families, our communities, and rewards our labor. Our apathy is our weakness, but we must churn it into righteous indignation.

It’s our salvation, a lifting of this nation’s soul from its ruins, a reconciliation between itself and the God who calls it over and over again to pursue justice, love mercy and walk humbly.

Perhaps now, on this Freedom Day, in this tumultuous time, we are ready to listen.

This is amazing....I'm soo proud of you son. Everyone needs to hear this.

What a gorgeous pice of truth so eloquently written. Your work resonates all the way down to Guatemala City, where I live. This rings true beyond the US context. I am saving this post for sure! Thank you!