The Mayor Who Fumbled It All

An analysis of the four years of chaos, dysfunction, and pettiness under the four years of Lori Lightfoot's Mayoralty of Chicago. "When the Fire was Upon Us" Part II

A running joke in Chicago politics is that there is something about crossing the threshold of the Mayor’s office on the fifth floor of City Hall that can make even the most well-intentioned politician an authoritarian machine boss.

Perhaps that can explain the radical transformation in policy, rhetoric, and conduct that outgoing Mayor Lori E. Lightfoot demonstrated over her four tumultuous years in office.

Indeed, any Mayor who made as many promises to reform city government, fully fund public schools and affordable housing, fully implement the consent decree for the police department, and rely less on property taxes would’ve had a difficult job getting most, if not any, of those things passed in a fifty-member city council composed of people representing various interest groups. Then again, not every Mayor barges into office after winning 74% of the vote and all fifty city wards as Lightfoot did.

But if Lightfoot’s landslide victory was to be an indicator of how her mayoralty would turn out, it would have little to no effect on her political or public policy achievements.

If anything, Lightfoot would prove to be inept for the job she held, flip-flopping and breaking key campaign promises, refusing to comply with FOIA requests, antagonizing the city press, struggling to retain city hall staff, breaking trust with organizations and cohorts of voters whose support she desperately needed, and hemorrhaging relationships with members of the City, Cook County, and Illinois State government; all the while maintaining that the majority of criticism levied against her and her administration was “because she was a Black woman”.

But how? How did a reform, good-government, seemingly progressive candidate ruin her mayoralty and fall from grace so dramatically, to the point that she came in a humiliating third-place finish in her re-election bid?

Surprisingly enough, Lightfoot’s troubles began before she even took office, and things just never seemed to get on track after that…

Lincoln Yards: Yay or Nay?

The Lincoln Yards project had been one of the most contentious economic development issues in the immediate aftermath of the 2019 campaign, although the ideological breakdown of who was for and against the project was much murkier than past deals.

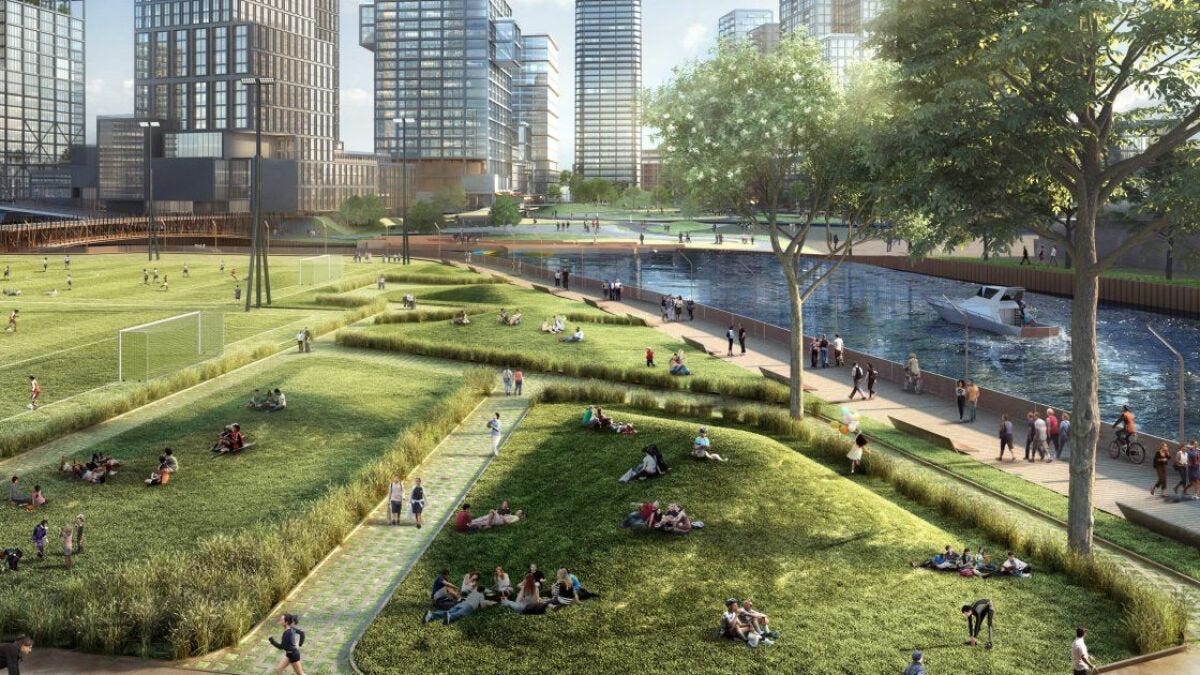

The development plan would cost $6 billion in total, with $900 million of those dollars coming directly from the city’s Tax-Increment-Financing (TIF) program, a set-aside city expenditure to fund community development programs, mainly in low-income and underserved neighborhoods.

Lincoln Yards had a mixed reception in both conservative and progressive camps within city government. Some argued that the TIF money could be spent elsewhere, others that green spaces were lacking in the original plan (which was later revised by the developer Sterling Bay), and still others that community input was severely lacking and that the project was being needlessly rushed by Mayor Rahm Emanuel and his corporate-friendly allies.

Progressive activists, however, were uniformly opposed to the deal and expected their Mayor-elect to back their calls for more investment on the South and West sides and to end corporate welfare.

For her part, during and after the election, Lightfoot had played her cards carefully. She refused to outright oppose the deal, only vaguely saying that she supported more community engagement, and criticizing the Emanuel administration for a lack thereof. Her tepid statements, including a request to delay the vote on the real, led many to believe that she would, indeed, oppose it altogether.

Shortly thereafter, Lightfoot eventually broke her fence-sitting posture and backed the deal, which passed 32-13, over the objections of many of Lightfoot’s voters.

With the Lincoln Yards project, Lightfoot could at least claim that she had never said “no” to the deal and that she had won some concessions for women/minority-owned contractors. Still, her vague opposition beforehand and her quick reversal of that opposition after the fact led some to wonder how authentic Lightfoot’s progressive bona fides really were. Would she be a reliable progressive on the fifth floor or break backroom deals like previous mayors?

However, Lightfoot’s Lincoln Yards confusion was nothing compared to her flip-flop on the much more controversial $95 million police training academy on the West Side that Mayor Emanuel had supported.

#NoCopAcademy…#YesCopAcademy?

The “Cop Academy”, as it came to be known, was slated by the Emanuel administration to be built in the West Garfield neighborhood, one of the poorest and violence-ridden neighborhoods in the city.

Local activists started the campaign #NoCopAcademy to protest and prevent the project, claiming that the $95 million could be better spent on violence prevention programs and mental health services. They also argued that the city’s handling of the Laquan McDonald shooting and subsequent federal consent decree, along with the history of racism and anti-Black violence within the CPD, made the building of a cop academy a gross insult to the community.

For a time, it appeared as though Lightfoot agreed with them.

During the first round campaign, Lightfoot had tweeted

I’ve said NO to Rahm Emanuel's $95 million cop academy since I got in this race…The failure to engage the community, while telling those same people there's no money for investments on the West Side, is unacceptable.

After her election, however, Lightfoot u-turned and went so far as to claim that the proposed $95 million in funding wasn’t enough.

Though her flip-flop and fence-sitting on Lincoln Yards had raised eyebrows, Lightfoot’s flip-flop on the cop academy deeply disappointed some of her campaign staffers, who were uncanny about Lightfoot’s repeated contradictory statements regarding the project.

In 2023, the cop academy opened in a grand ceremony, with Mayor Lightfoot proudly cutting the ribbon. By that time, the cost of the academy had risen to $128 million.

A Rookie Mistake

Every Mayor of Chicago is sworn in in mid-May, giving them two looming crises to confront immediately; they must develop an effective strategy with CPD and anti-violence community organizations to avoid or mitigate an anticipated spike in violence over the summer and they must secure a contract with the Chicago Teachers Union, or risk a late start to the school year, or worse, a strike.

Lightfoot mildly succeeded in the first task but failed miserably in the second. While she could boast of a slightly less tumultuous summer than her predecessor, her failure to secure a decent contract with the Chicago Teachers Union was just one of many rookie mistakes made in her first year in office.

The CTU and Lightfoot were already on sour terms. They had spent millions attempting to defeat her in the election and were still licking their wounds from the whole Preckwinkle debacle. They had been anticipating a contract dispute regardless of who was elected mayor, but Lightfoot’s election and her antagonistic attitude toward the union made a dispute, a work stoppage, or worse, a strike, a tangible cloud over the first summer of her administration.

It didn’t take long, then, for a dispute to make a turn for the worse. After the CTU-CPS contract expired, CPS proposed a 14% pay raise for teachers over five years, with the CTU counter-proposing for a 15% raise over three years. An independent fact finder, a crucial middle agency for labor disputes, proposed a 16% pay raise over five years with a 1% increase in healthcare contributions from the teachers. The CPS accepted it, the CTU rejected it. More subsequent conflicts over classroom sizes, nurses, psychologists, social workers, librarians, and funding for unhoused students ensued, proving to be even more contentious, and negotiations stalled heading into October.

The CTU continued rallying political support, hosting rallies and demonstrations across the city. Their efforts were even supported by presidential candidates such as Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, as well as then-former Vice-President Joe Biden.

For her part, Lightfoot claimed repeatedly that the CTU’s demands were unrealistic and unattainable, and that many of the proposals, specifically those related to housing, were not pertinent to the contract. She had a “responsibility to the taxpayers”, she claimed, not to overburden the budget with excessive spending. The CTU counter-claimed that Lightfoot herself had campaigned on almost all of their proposals and that her defensive posture proved that she was untrustworthy.

Lightfoot and her team failed to reach a last-minute deal and on October 16, the CTU officially voted to strike. A poll taken just a few days prior showed that more Chicagoans favored the CTU over the City. The strike would last for 14 days, becoming the longest teacher’s strike in Chicago history. On Halloween Eve, a contract was agreed upon, with the city making concessions to CPS on a plan for hiring more social workers, nurses, and librarians, and raising pay by 16%.

For Lightfoot, it was a political disaster and one that would constantly repeat itself throughout her tenure. Her posture during the strike had been similar to her predecessors. She engaged in verbal back-and-forths with the CTU leadership, positioned herself to the right of the organization to cover her tracks, and lost valuable political capital in the process.

She had proven herself once again to be a political flip-flopper, willing to abandon her progressive campaign promises on education when she believed it was politically expedient to do so, and unwilling to challenge the neo-liberal, deficit-hawk financial orthodoxy that had ruled City Hall for the last three decades, starving public schools, public health services, and public housing of desperately needed resources.

Lightfoot, the reformer, was revealing herself to be more of a Jane Byrne than a Harold Washington.

COVID-19, Cops, Bridges, & Anjanette Young

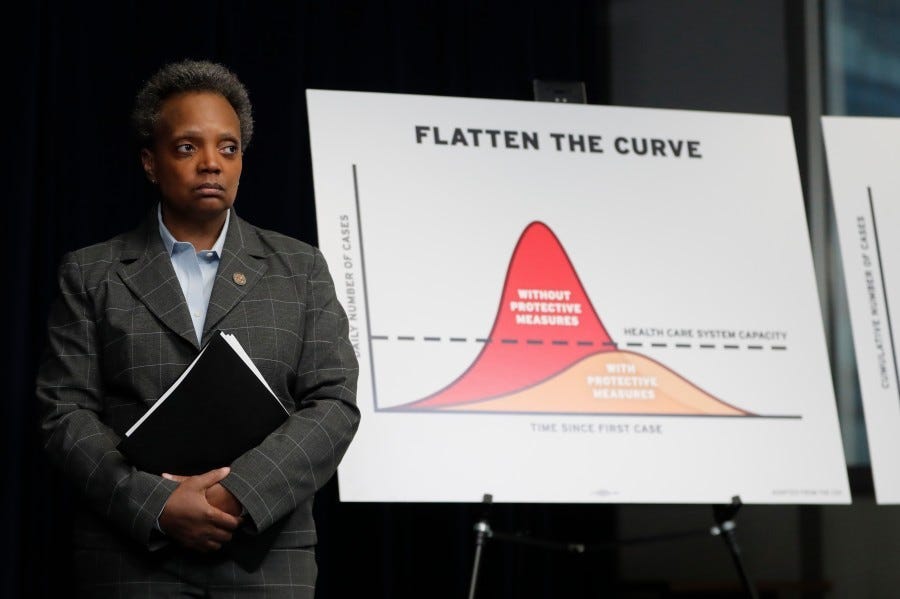

The COVID-19 pandemic was an unprecedented and barely mitigated disaster in every part of the world, and it particularly devastated American cities. Chicago was no exception.

Lightfoot had ordered the city into lockdown in late March of 2020 and had firmly established broad executive powers for herself as she and others struggled to mitigate the effects of the pandemic. Almost overnight, a city known for its vibrancy and bustling communities became a ghost town, as COVID infected and killed hundreds, and then thousands of Chicagoans, mostly Black and Brown Chicagoans.

Though the pandemic thoroughly exhausted the Lightfoot Administration and stretched the city’s already subpar services to their thinnest, it was also a rare political opportunity for the Mayor’s image to rebound.

Lightfoot’s decisiveness, directness, and refusal to compromise on COVID restrictions in the early days of the pandemic endeared her to Chicago residents, and her approval rating shot up to 78%. It was in stark contrast to the bumbling chaotic mismanagement and deadly incompetence of the Trump Administration, which refused to take the pandemic seriously, which led to hundreds of thousands of American deaths.

But all of Lightfoot’s political fortunes were about to come to an abrupt halt, when, in the aftermath of the gruesome murder of George Floyd, Chicago’s Black community and their allies erupted.

The George Floyd uprisings that took place throughout the United States and around the world shook the very fabric of the modern state, amplified an already burgeoning modern Black freedom movement, and firmly put questions of poverty, extreme inequality, racial capitalism, and carceralism under a microscope. It changed everything, and the fact that it took place alongside a once-in-a-lifetime global pandemic only served to strengthen its impact. To date, it is the largest protest movement in American history.

Chicago, a breeding ground for one of the most militarized police forces in the nation, with a detailed track record of rampant racist misconduct and abuse, and with a horrific racial past and present, was no exception. If anything, it was a bellwether, and Lightfoot’s Administration, though one of the most diverse in Chicago history, was totally unprepared for it.

Lightfoot herself struggled to balance decisiveness with justice, and her response to mass peaceful protests and rage-fueled rioting and looting across the city was symptomatic of this internal struggle.

Subsequent reports revealed that the CPD was woefully unprepared for the protests and that they had used excessive force and brute violence to quell the demonstrations, endangering local businesses and residents.

The raised bridges proved a political disaster for Lightfoot, intensifying her already poor relationship with activists and the city’s grassroots, causing chaos within the ranks of the CPD, and creating an atmosphere for political opposition on both the right and the left. For a Mayor who had promised to reform the Chicago Police Department and to fully implement the federal consent decree imposed on CPD in 2016, the George Floyd uprisings served as a visible reminder of just how far the police department was from such “reform”. It also revealed Lightfoot’s willingness to rhetorically embrace progressive language about “equity” and “reform” while continuing business as usual, expanding police powers and her own, and betraying her campaign promises once again in the process.

It was a fatal error from which she would never recover.

When CBS Chicago obtained video footage of a February 2019 botched CPD raid of the home of a Black female social worker and attempted to air it, the Lightfoot Administration, through her Corporation Counsel Mark Flessner, sought to block its release.

When Chicago Tribune reporter Gregory Pratt uncovered this, the video aired on the CBS local news on December 14, 2020. The video showed heavily armed officers raiding the social worker’s, whose name was Anjanette Young, home while Young had just exited her shower. Young was handcuffed and stood naked and exposed for several agonizing minutes before she was covered up with a blanket, as she tearfully screamed and begged police to exit her home, telling them that they had the wrong house.

Indeed, the officers present did, in fact, have the wrong house. Young’s address had been pinned by mistake. But the trauma of the gruesome and violating raid was already done, and millions of Chicagoans and people around the country watched the viral video in horror.

Lightfoot’s response was that typical of politicians in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. She lamented the obvious case of brutal racist violence against Young, saying that she resonated with Young’s pain as a fellow Black woman. She also sharply criticized the law department’s attempted blocking of the video’s release and apologized to Young.

These were not the crux of Lightfoot’s remarks, however. Her most striking claim was one of innocent ignorance, that she had not seen the video nor known about the raid until a staff member told her about it on December 14, the same day the video of the raid was aired on local news.

This was already difficult to believe, given the Mayor’s proximity and access to confidential briefings between the Office of the Mayor and the Chicago Police Department, as well as the Corporation Counsel, who serves as the city’s chief litigator and head of the law department.

The initial skepticism from the public and the press concerning Lightfoot’s original statement would be proven well-founded, and Lightfoot was forced to retract her remarks, admitting that indeed, she did know about the Young raid over a year before when she said she did, with later-released text messages revealing that she had even referred to the matter as the “Rahm raid”, even blaming the Chicago Teachers Union for the subsequent political fallout.

The raid and the Lightfoot Administration’s attempt to cover it up led to the Corporation Counsel’s resignation on December 20 and Lightfoot’s worst political crisis to date. Her honesty, integrity, and that of her administration were all fully in question, and the calls from the press, independent watchdogs, and Young herself for more transparency, justice, and accountability only amplified Lightfoot’s problems.

A year later, a scathing Inspector General’s report found that multiple city agencies and departments not only mishandled the Young raid but deliberately misled the press in the aftermath. The Lightfoot administration had engaged in “unbecoming behavior” and “insufficient and wasteful management”.

Lightfoot rejected the findings.

Things Fall Apart (2021-’22)

Lightfoot and Alderwoman Jeanette Taylor engage in a viral heated exchange in City Council chambers. June 23, 2021

2021 saw Lori Lightfoot’s political standing significantly weaken.

Violent crime surged across Chicago and most of America’s major cities, the COVID-19 pandemic continued to run rampant despite reopening and vaccines, and dissatisfaction, exhaustion, and anger mounted against the Mayor for failing to fulfill key campaign promises, from housing to education to police reform.

Lightfoot also lost many close City Council allies, who were fed up with the Mayor’s tyrannical leadership style and found herself scrambling to get to 26 votes on even the most mundane tasks of city government.

Perhaps no public event signified just how far Lightfoot had fallen from grace than a June 23, 2021, City Council meeting.

The Council was already in a tense mood, as they were planning to vote on a highly contentious resolution to rename Chicago’s infamous “Lakeshore Drive” to honor the city’s first non-indigenous settler, the Haitian explorer Jean-Baptiste Du Sable, a folk hero in Black Chicago.

Lightfoot was also seeking the Council’s support in confirming her pick for a Corporation Counsel to replace Flessner, Celia Maza.

Lightfoot, thin-skinned and not wanting to be reminded of a political embarrassment, angrily confronted and accosted Taylor on the Council floor. Taylor defended herself, angrily telling the Mayor to get out of her face. Pictures and an inaudible video of the exchange went viral, embarrassing Lightfoot yet again.

While it was not uncommon for Mayors to have tense moments with their City Council colleagues, sometimes to the point of verbal showdowns, it was uncommon for a Mayor to leave their Chair to confront an individual alderperson.

The Jeanette Taylor exchange was only one in a series of bad decisions and bad press the Lightfoot administration had received, from all sides of Chicago’s political spheres.

Crime was rising, and rising fast, with homicides and carjackings at near-record highs. Though post-pandemic crime rates were rising around the country, most Chicagoans laid the blame for low police morale, community disinvestment, and bare-bones violence prevention squarely at the Mayor and her appointed Superintendent, David Brown’s, feet.

Lightfoot and Brown did nothing to assuage the fears of Chicago residents, choosing instead to regurgitate largely debunked right-wing talking points, blaming crime on pretrial release and other criminal justice reform measures instituted by reformist Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx and the supposed lethargic sentencing of gun offenders by Cook County Chief Judge Tim Evans.

It hardly mattered, of course, that these attacks on criminal justice reforms not only mirrored the far-right rhetoric of characters like Donald Trump and Ron DeSantis, nor the more important fact that these accusations were blatantly and provably false. Lightfoot and Brown continued to perpetuate the canard.

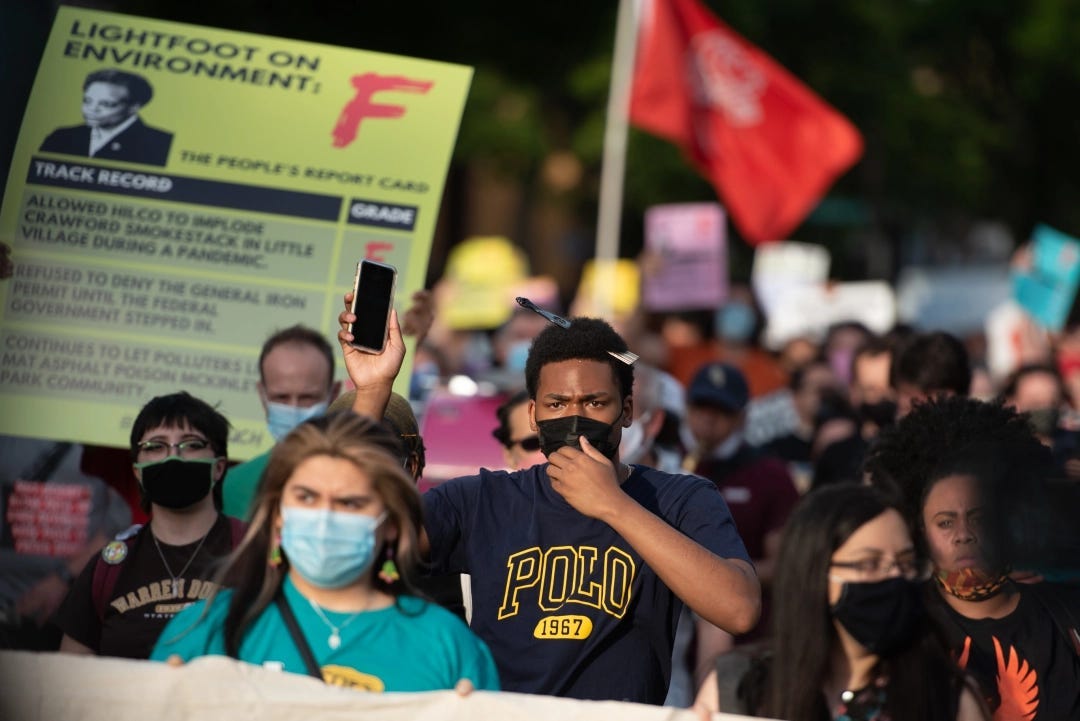

Adding to Lightfoot’s woes was the increasing frustration of progressive organizations and activists at her refusal to support policies she explicitly campaigned on in 2019. On everything from affordable housing, to reopening the shuttered mental health clinics, to police reform, to an elected school board, Lightfoot had either flip-flopped, reversed herself, or qualified her previously unqualified support. She also managed to give $1 billion in COVID relief funds to the CPD, further infuriating stratified and vanquished social service providers, who served in communities desperate for funding.

When pushed, Lightfoot doubled down, employing her Mayoral powers over committee hearings and the budget to actively halt the implementation of progressive policies. Her actions infuriated the city’s left wing, and they began actively searching for someone to challenge Lightfoot in 2023. She had gone from cautious friend to most wanted enemy.

The City’s right-wing, too, seized on Lightfoot’s failures to manage crime and her proposal to remove a Christopher Columbus Statue, leading Lightfoot to privately berate a city official for wanting the statue included in an Italian-American parade, saying

Lightfoot’s beratement of Taylor, then, was merely the culmination of an erratic Mayor becoming increasingly difficult to work with, a petty tyrant who demanded much and accomplished little, a promise-breaker who had turned her back on working-class Chicagoans, and an incompetent administrator who bled staff members, alienated key allies and created more barriers to her own progress than even her worst political enemy.

All Lightfoot could say to defend herself was that “99% of the criticism” she received was because she was Black, she was Queer and a woman.

It was to become a common moniker of Lightfoot’s, and one that rang hollow as Black Chicagoans struggled with the daily realities of poorly funded public services and schools, Queer and Trans youth faced homelessness, and Chicagoans of all genders struggled to get to and from work and home on an unreliable and chronically under-resourced CTA.

Chicago Decides (2022-’23)

On June 7, 2022, Lori Lightfoot announced her intention to seek a second term as Chicago’s Mayor. In an announcement video, Lightfoot took on her critics head-on, saying that although “people may not always like” her delivery, she still had a record of accomplishment, from ethics reform to a $15 minimum wage, and her most well-known program, “Invest South/West”, a multi-billion dollar public-private partnership agreement designed to fund development projects in Chicago’s most neglected neighborhoods.

No one could reasonably dispute that Lightfoot had indeed developed a list of accomplishments over her term. However, the fact that few Chicagoans could name those accomplishments, much less feel their effects, was indicative of a Mayor too preoccupied with point-scoring with her political opponents, cursing out Aldermen, and breaking major campaign promises, that she had forgotten to remind the 2.6 million Chicago residents she served that she had delivered on some things.

The Great White Hope

For all of her talk of “delivering” for Chicago’s working class, Lightfoot’s failures and demeanor had already alienated large swaths of voters, voters she would need to win a second term in the February 28 preliminary and subsequent April 4 runoff election.

White Chicagoans had formed the bulk of Lightfoot’s catapult from third-tier contender to Mayoral front-runner in 2019, yet most of them had abandoned her by the time of her re-election launch. They felt that their fears over crime and public safety, an issue that would dominate the race, had gone ignored by their Mayor and that she had turned her back on the CPD through her minimal attempts at reform.

They looked instead for a White Savior, to resurrect from the ashes of multiculturalism and the post-Obama consensus of the myth of the “competent White man”.

They found it in Paul Vallas, a right-wing ideologue, noted school privatizer, frequent career failure, and machine loyalist who prowled around with far-right-wing organizations like Awake Illinois, railed against taxing the wealthy and relied on racist crack-epidemic era rhetoric to galvanize his white ethnic base.

Vallas had announced his candidacy only a week before Lightfoot and was seen as a major contender for the conservative bloc of Chicago voters.

Though Vallas had failed to gain traction in his previous run for Mayor in 2019 (where he had subsequently endorsed Lightfoot in the runoff), this time Vallas could rely on Chicago’s corporate class to bankroll his campaign of Nixontonian crime fear-mongering, Clinton-Reaganesque neoliberal and privatization policies, and a sense of unearned and shameless bravado to top it all off.

If Vallas couldn’t win on his abysmal record of privatizing public services and running up mountains of debt in cities and school districts around the world, he could certainly rely on money to patch up his image.

The Left’s Pick

Meanwhile, progressive Chicago was searching for a left-wing challenger to Lightfoot, to drown out the crime-hysteria talking points of actors like Vallas, and to chart a progressive vision for fully funded public services and schools, investment in neighborhoods, and police demilitarization.

Two progressive organizations, the CTU, and United Working Families, were especially anxious to find a credible challenger, so much so that by the time campaigns began launching in mid-late 2022, they already had one lined up.

Westside Cook County Commissioner Brandon Johnson was unlike any candidate that Chicago’s left flank had run for high office in nearly four decades.

For starters, he was already one of theirs. He had been a part of grassroots and organizing spaces for most of his adult life, working for CTU as an organizer and serving on the front lines of the movements against privatization and school closures.

He hadn’t some “come to Jesus” moment as had many other progressive politicians. Well before he ran against and barely beat incumbent Commissioner Richard Boykin ( a loyal stooge to the corporate class), Johnson has been a bonafide and consistent member of Chicago’s leftist circle.

He was also charismatic, good-natured, charming, friendly, and genuine, something that made him a likable as well as principled candidate. He announced his campaign near Cabrini Green, the infamous site of Chicago’s experiment in communal starvation and racist housing and education policies, where he had served as a school teacher.

He launched into a series of attacks on Lightfoot, calling her a “promise breaker”, while also pledging to be a champion of Chicago’s left-behind working families, supporting prominent progressive proposals like “Treatment, not Trauma”, an ordinance designed to treat public safety as a mental health crisis with funding for social workers to respond to non-emergency police calls, and “Bring Chicago Home”, a real estate transfer tax on luxury home sales to fund affordable housing.

Even better for Johnson, the American Federation of Teachers had already agreed to give him $1 million as seed money to build a large grassroots campaign, something he would need with such low name recognition.

The media would initially ignore him, as would Lightfoot, Vallas, and most of the other candidates (there would be nine in total), but, as they all realized far too late to stop him, Brandon Johnson was the wrong candidate to underestimate.

One Term’s A Charm

Perhaps Lori Lightfoot never really stood a chance. Her approval rating was too low, crime was too high, and Chicago was too exhausted to keep her on the 5th Floor of City Hall for another four years.

The campaign had been brutal, with Lightfoot taking punches from every which way and making no shortage of disastrous blunders.

For starters, she had focused most of the campaign on attacking her opponents, mainly Congress Chuy Garcia, who, after being egged on by close friends, had reluctantly decided to enter the race, without any support from the progressive grassroots that he had had eight years prior in his bid against Emanuel.

It made sense at first; Garcia was an obvious front-runner on name recognition alone, and at first glance, it seemed as if he was competing for the same voter demographic that Lightfoot had relied on in 2019; disaffected wealthier white North-siders.

However, after a couple of expensive TV and internet ads linking Chuy Garcia to failed corrupt crypto-currency businessman and alleged fraudster Sam Bankman-Fried were run by Lightfoot’s camp, Garcia’s poll numbers began to slump. His lackluster campaign and clumsy attempts at triangulating between Chicago’s progressive and conservative camps did little to help him, and he was relegated to an embarrassing fifth-place finish in the first round.

Garcia’s numbers had slumped just in time for Brandon Johnson’s numbers to rise, but Lightfoot wasn’t prepared to take on Johnson, who had begun the campaign polling at a dismal 2%. He had more money than she did, and his ads painted him as a regular, everyday Chicagoan with a bold, progressive vision for the city’s future. He had also released a platform designed to appeal to Chicago’s working class; taxing the rich, funding public schools, reopening mental health clinics, and a whole host of other policies.

It didn’t help things that one of Lightfoot’s top Black City Council Allies, the moderate Alderwoman Pat Dowell of the Southside, had endorsed Johnson. Black Chicago was Lightfoot’s Hail Mary, and with Black conservative businessman Willie Wilson, a perennial candidate and reactionary, in the race as well as Johnson, her base of support with that demographic was in serious jeopardy.

Lightfoot’s campaign also made a series of silly mistakes, like sending an email to CPS students recruiting them to work on her campaign (which is against the law), or telling an audience of Black Chicagoans on the Westside “not to vote”, if they didn’t plan on voting for her.

Both of these incidents revealed a campaign lacking in message, direction, and vision, and for all her talk about Invest South/West and the $15 minimum wage ordinance, Chicagoans were still struggling to wrap their heads around the sheer number of promises Lightfoot hadn’t kept.

It all culminated in Lori Lightfoot becoming the first Chicago Mayor since Jane Byrne to be denied a second term, failing to make the runoff and coming in third place (with about 17%) to Johnson’s second place (at 22%) and Vallas finishing in first (33%).

After a gracious concession speech to both Johnson and Vallas, Lightfoot largely vanished from the political scene. She wouldn’t hold another interview with the press until Brandon Johnson was only days away from being sworn in as Chicago’s new Mayor.

What’s The Lightfoot Legacy?

Chicago Mayors are a historically difficult group of people. They are hard-nosed politicians, aggressive and assertive decision-makers, and all of them have just a hint of bravado in daring to run for the job in the first place.

Chicagoans don’t elect our Mayors to be “nice” people, someone who’ll make for a good dinner party guest, (although this is certainly a nice perk), nor do we want our leaders to be cruel and offensive like a 1920s gangster or that one relative who we don’t call because they’re kind of a jerk.

The 2.6 million people who call Chicago home, of which roughly a third participate in municipal elections, elect a Mayor to deliver for us, especially the most vulnerable; to look out for our unhoused friends and neighbors, to make sure our children have access to a fully- funded and well-resourced public school by day and can take a reliable train home at night without worrying for their safety, to make the wealthiest people who rake in billions off the labor of hard-working Chicagoans pay their fair share of taxes so we don’t have to borrow that extra $300 to foot the property tax or rent bill at the end of the month, to guarantee access to a public mental health clinic, so that even in our darkest moments, we can still count on a helping hand, and to keep the CPD from raiding our homes, harassing our kids, and killing us.

Chicagoans know we ask for a lot because we know we deserve a lot. After all, who made Chicago great in the first place? It wasn’t the Titans of Industry we see propped up so often in romanticized fiction, it was working-class union workers, Black refugees from the Jim Crow South, Latine and Asian immigrants, and the Indigenous peoples who were here all along. We know, then, that we are well within our right to demand that a city that was built by working people works for working people.

Lightfoot’s legacy, therefore, rather than succumbing to the all-too-easy national media obsessions, was tarnished not because she swore too much, or was too “aggressive” in her approach, but because she let us down. She led us to believe that she was on our side, that she heard our cries for a city that really worked for all of us, and that she understood the need for a bold agenda to match the enormity of the crises we face as a city and as working-class people, and that she’d be our advocate.

While we can certainly laud the achievements of a Black Queer woman who overcame substantial systemic and institutional barriers to achieve the highest office in the third-largest city in the nation, it is equally important that we acknowledge that “representation” is, in fact, not enough, and that it is wholly insufficient and inadequate to meet the needs of Chicago’s most blighted communities. Having a seat at the table can only get us so far when that seat is occupied by someone whose power analysis is inherently interlinked with racial capitalism, militarism, and neoliberalism.

Perhaps no politician represented this deficiency more so than Lightfoot. Very few big-city Mayors can claim the mandate and the mantle that Lightfoot was given when she was sworn in on May 20, 2019. She had won 74% of the vote and had a unique opportunity to be America’s most forward-looking and progressive mayor. Finally, the prevailing orthodoxy of financial scarcity for public services and plentiful resources for carceralism could have come to an end.

Nothing can explain her failure to meet this opportunity head-on other than a simple lack of willingness to do so; a mixture of personal arrogance, bravado, entitlement, professional incompetence, and ideological latitude that lent itself to the corporate class and the elites of a city that are hell-bent on keeping themselves in permanent control at all costs.

The Lightfoot legacy, then, is one of a missed opportunity, and a series of broken promises to Chicago’s working class. But, perhaps more startingly, it is one of institutionalized trauma and pain at the hands of someone who should’ve known better, someone who the people elected and trusted to do better.