When the Fire Was Upon Us: (How'd We Get Here?)

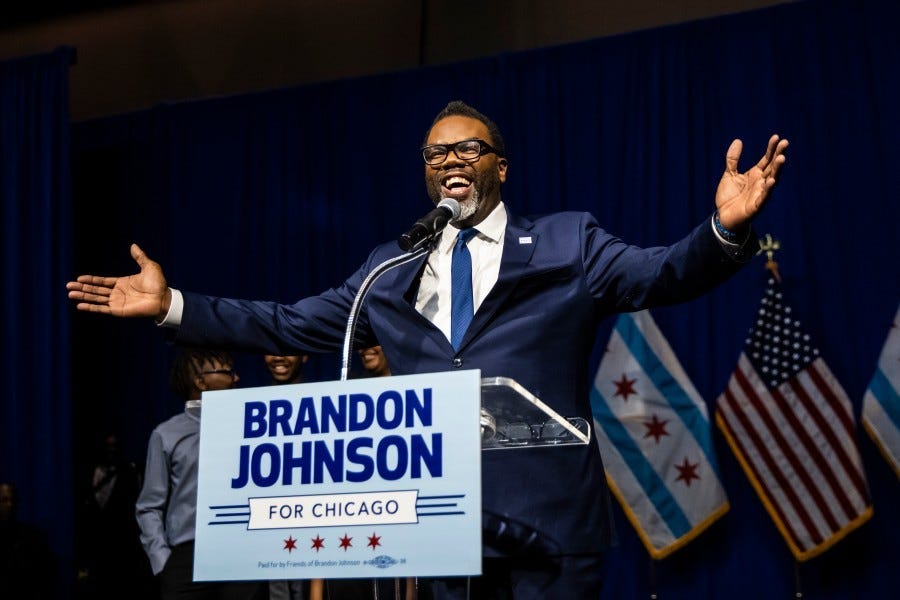

How a multiracial, working class movement resurrected and elected Brandon Johnson as Mayor

On April 4, Chicagoans faced the most consequential electoral decision they’d had to make in four decades. On the right was Paul Vallas, the right wing ideologue who had spent most of his career privatizing public schools and cozying up to right wing corporate elites, while leaving working class communities, predominantly those of color, starved for resources and investment.

Throughout the campaign and in the months prior to its beginning, Vallas spent much of his time prowling around on right-wing radio stations, playing devil’s advocate for Donald Trump, and associating himself with the architects of Chicago’s decline; those who’ve spent the past three decades promoting an agenda of privatization, carceral systems, and corporate welfare.

On the left was Cook County Commissioner Brandon Johnson, a staunch progressive legislator and Chicago Teachers Union organizer, who ran on investment in social programs, taxing the rich, and focusing on crime prevention and interruption rather than militarized policing.

While Vallas was backed by right wing corporate donors such as Ken Griffin of Citadel, far-right fascists such as Charlie Kirk and Fraternal Order of Police president John Catanzara, as well as a whole host of Democratic party machine operatives Johnson was backed by the CTU, SEIU local, the American Federation of Teachers, United Working Families, dozens of local neighborhood Independent Progressive Organizations (IPO), and a whole host of other grassroots progressive organizations who spent millions in small-dollar donations running ads, knocking doors, and phone-banking on his behalf. (Even still, Vallas outspent Johnson 2:1).

When the votes started to pour in last night, Vallas led Johnson 53-47, while the predominantly Black wards on the west and south sides lagged behind in reporting. By 8:30 pm, Johnson had taken a narrow lead, and by 9:30, the Associated Press had called the race, solidifying Johnson’s victory.

The Chicago press’ behavior toward the most progressive Black candidate elected Mayor of a major city in 40 years was nothing short of embarrassing.

Throughout the brutal and ugly campaign, Johnson was attacked vehemently by opponents and the media alike for being a “radical” who wanted to “defund the police”, was hyper-criticized for every campaign slip up, every poorly worded interview answer, and every debate performance, and had his tax and spend proposals dragged through the mud by every mainstream media outlet.

From start to finish, the press framed this race as one mainly about crime, and uncritically interpreted polls suggesting that crime was the number one issue for Chicago voters as a sign that Chicagoans wanted more police hires, a more militarized and empowered police department, and an even higher police budget.

They spent hours worth of time and ink manufacturing consent for a right wing reactionary candidate like Vallas to take the mantle of Chicago’s “knight in shining armor”, while completely ignoring the actual policy goals of the communities most affected by crime; mental health services, public school funding, and violence interruption.

While Johnson’s ties to the Chicago Teachers Union took up much of their reporting from the very beginning of his campaign in November, the mainstream Chicago press refused to hold Vallas’ record of school privatization, mismanaged city budgets, and far-right ties as recently as early 2022 to the same light of scrutiny. Johnson was forced to answer for every policy proposal issued by his backers, including one proposal for an income tax on city residents that Johnson never advocated for and explicitly stated he would not pursue.

Vallas was not asked to answer for Ken Griffin and Citadel’s opposition to the progressive income tax proposal by Governor JB Pritzker, the millions of dollars Citadel made in profits from gun manufacturing investments, the proposals to “defund” the Chicago Public Schools that he himself liked on his Facebook account, or the racist and outlandish attacks that many Vallas supporters and donors had made against Cook County State's Attorney Kim Foxx, a Black woman. Vallas saw the media give him mostly a free ride; accepting his narratives on crime and policing and refusing to critique his record of failure and administrative incompetence in four major cities that he had worked in. Instead, the press called Vallas a “centrist”, and a “policy-wonk”.

It was very clear to any observer who was paying close attention that Johnson’s win was a political earthquake; an astounding defeat of the corporate establishment and a huge victory for the city’s progressive and Black movements. But how did the grassroots, the Black freedom movement and the labor movement come together and resurrect their electoral power?

To answer this pivotal question, it is crucial to explore the history leading up to April 4, 2023.

Reclaiming Their Voice: The CTU Strike & Rahm Emanuel

The Black freedom & Labor movements in Chicago reclaimed their voice in 2012, when Mayor Rahm Emanuel proposed a dramatic austerity budget that closed 50 Chicago Public Schools, laid off hundreds of staff, increased required pension contributions, and shuttered most of the city’s publicly owned mental health clinics.

Led by the late Karen Lewis, the Chicago Teachers Union led the largest and most consequential teacher’s strike in a generation, shutting down public schools for 7 days and winning concessions on retaining veteran teachers and striking down “merit-based” pay based on test scores. Aided significantly by Lewis’ dynamic leadership style, political brilliance, and charisma, the CTU won the hearts and loyalty of thousands of Chicagoans, mainly Black Chicagoans, through neighborhood organizing, community engagement, and relationship building among parents and students.

Their confrontational negotiating and protesting style, as well as President Lewis’ ability to captivate audiences and shift the narrative on public school funding, made the strike a lightning rod for resistance to neoliberal economic and social policies in American cities, and made CTU one of the most powerful progressive institutions in the country.

On the flip side, it also made the CTU a detested and formidable adversary among Chicago’s corporate class, who had spent millions on Emanuel’s 2011 campaign for mayor. Many donors to Emanuel, including David Herro (who founded my charter middle school), stood to benefit from Emanuel’s privatization schemes, as public dollars poured into privately-run charter schools without the ability for teachers and staff to collectively bargain and without crucial oversight from the city were deemed a safer financial bet than traditionally-run public schools.

Thus, the CTU stood at a positional crossroad; being both a strongly supported progressive organization among Chicago’s Black working-class families and the number one target of right-wing attacks.

The Chicago press dutifully played their usual role of carrying water for the elite, criticizing CTU both during and after the strikes, and framing the organization as dysfunctional and arbitrary. Most ironically, many in the press framed the CTU’s demands on school funding, teacher salaries, and wrap-around services not only as unaffordable but “anti-progress”. To them, Rahm Emanuel’s policies of neoliberal austerity and giveaways to charter school funders were the “change the city needed” and the CTU’s demands of fully funded neighborhood schools were the “failed status-quo”.

Ludicrous as it was and is, this line of attack worked brilliantly in wealthier, whiter parts of Chicago, and have given many residents in those communities the ammunition they need to oppose not only progressive education policies, but progressive goals more broadly. The strength of the Black Labor movement, exemplified in the CTU strike of 2012, would serve as a catalyst for the ongoing and brutal war between Chicago’s progressive movement and its corporate elite.

Though the CTU could claim victory in the court of public opinion, it suffered several major electoral defeats that undercut its success and made it even more ripe for bad-faith attacks.

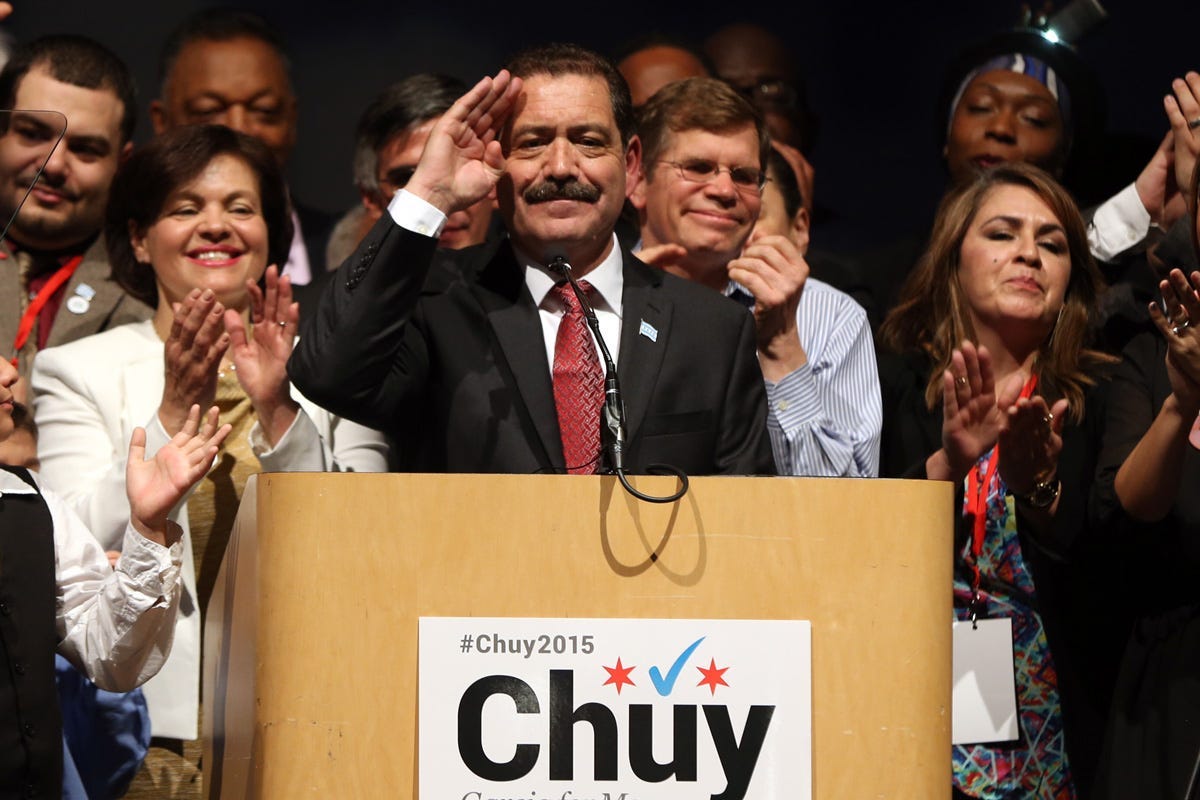

In 2015, after Karen Lewis fell ill with cancer, the CTU endorsed then-Cook County Commissioner Jesus “Chuy'“ Garcia to run for Mayor against Rahm Emanuel.

Emanuel’s education and healthcare policies had made him vulnerable to a challenger, and many on the left hoped that Garcia, though not an ideal candidate, would manage a victory over Emanuel and institute a new era of progressive governance that matched the enthusiasm of the 2012 strikes.

However, though he managed to force Emanuel to a runoff, Garcia struggled immensely with Black voter outreach and organizational discipline. Emanuel was successfully able to outraise, outspend, and out-compete Garcia, in addition to defining Garcia and the progressive movement at-large as “unaffordable” and fiscally irresponsible.

For Black Chicagoans, who had for decades borne the brunt of every horrendous financial decision the city made through cuts to public services and tax hikes, the risks of a Garcia mayoralty were seemingly too much to bear. Emanuel won the runoff election by double-digits, with overwhelming support from whites and comfortable support from Blacks. The CTU emerged stronger than ever, but bitterly disappointed.

Missing the Moment: The 2019 Election

In 2019, when Emanuel chose not to seek a second term amidst mounting unpopularity due to his handling of the police murder of Laquan McDonald, and the rise of the democratic socialist and grassroots progressive movement in Chicago, the CTU found itself in a potentially defining moment, with no candidate.

Though Chicago Public School principal and Bernie Sanders surrogate Troy LaRaviere initially showed promise, he failed to garner enough support to appear on the Mayoral ballot. Chuy Garcia had already committed to a congressional bid. With a wide open field of contenders, mainly from the right, the likes of Bill Daley, Gery Chico, and yes, Paul Vallas, and with an increasing focus on ethics and corruption in the wake of the indictment of long-time machine Alderman Ed Burke, the CTU had to make a split-second decision; either pick an unknown and amplified their status or pick a well-known politician and hope they get lucky. They settled on the latter option.

Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle was no progressive’s first choice for mayor, and she ranked even lower as a potential mayoral candidate. For her part, Preckwinkle could boast of some major progressive bona fides.

She had served Hyde Park’s alderman for nearly twenty years, developing a reputation as one of the City Council’s furthest left members, a low bar but important accomplishment. Preckwinkle particularly drew praise for bucking Mayor Daley’s more controversial parking meter deal.

In 2010, Preckwinkle defeated incumbent Todd Stroger and three other candidates to become the President of the Cook County Board of Commissioners, the chief executive of Cook County government. It was there that her progressive bona fides began to fade, as Preckwinkle cozied up the Democratic Machine, slashed the county budget, laid off hundreds of decade-long serving county employees (disproportionately Black professionals), and refused to join the progressive movement as they rallied to oppose the austerity agenda of Mayor Rahm Emanuel.

By 2018, when she announced her candidacy for Mayor, Preckwinkle had become widely known not as an independent progressive county executive, but as a ruthless political pragmatist who conformed to the status quo of neoliberal budgetary and political orthodoxy, a reputation that was perfectly manifested in the unpopular and quickly repealed "soda tax”.

The CTU and other organized labor organizations’ decision to endorse Preckwinkle came under fire from many on the left, who argued that Preckwinkle was not only insufficiently progressive in her governance but too far too cozy and close to Democratic machine politicians like Ed Burke, notoriously corrupt Cook County Assessor Joe Berrios, and a whole host of other machine politicians, in an election where trust in public servants was at an all time low.

The endorsement backfired, and set the CTU back electorally. Preckwinkle would go on to run a truly horrendous and incompetent campaign, having to fire several senior staff, walk-back inflammatory comments from campaign surrogates, and pull television ads just days before the runoff election. In the end, Preckwinkle would only garner 26% of the vote compared to 74% for a little-known bureaucratic lawyer-turned reform politician Lori Lightfoot.

Lightfoot had run on an anti-machine, good government, and progressive platform, and had come out of nowhere to win the race. She had cleverly used her name to promise to “bring in the Light” and to end the decades-long practices of shady backroom dealing and anti-working class politics that had left so many Chicagoans starved for resources and opportunity. She had supported an elected school board, police reform, neighborhood investment and a fairer tax system, all of which had won her praise from moderates on the Northwest side, progressives in the Lake Front, and Black voters on the West and South sides.

With a huge mandate, Lightfoot was emboldened and greatly empowered to make sweeping changes to city government. Once she took office, however, Mayor Lightfoot sang a remarkably different tune.